Tags

Canterbury Union Bank, Elizabeth Baldock, Flemish School, Loutherbourg, Mieris, Murillo, Petham, Van Goyen, William Baldock, William Henry Baldock

The peak of William Baldock’s success was embodied in the House at Petham. It was designed on such a grand scale that when the family finally sold, the new owners demolished parts of the estate because it exceeded anything they could usefully use.

The ambition behind Petham was perhaps a curious one for a man who had kept such a low profile, planned meticulously, and lived a quiet and secretive life. Perhaps William felt he wanted to finally make a statement about his success – how he had grown from a reputed cowherd on the Seasalter marshes and hod carrier in Canterbury to become one of the richest men in Kent.

One theory behind this overt display of wealth is that William bought Petham and expanded on it to avoid taxes on his estate. At the end of the 18th and into the early part of the 19th century, property and land were exempt from inheritance tax. Of the £1.1million legacy that William left behind only £100,000 appears to have been in liquid assets and cash. (Much of his inheritance and tax planning also involved setting up complex trusts for nephews and nieces.)

Over the years, William had invested in properties and land stretching from the Isle of Sheppey to the town of Deal. Quite a few of these investments involved smallholdings in remote parts of Kent – useful hiding places for contraband.

The property at Petham was William’s most ambitious project.

Sitting above the village, the House was designed to impress but also ensure privacy.

In ‘An Epitome of County History, Kent’ (Vol.1) published in 1838 we are told:

“Petham, in the Parish of Petham, is the seat of William Henry Baldock, Esq. a Magistrate and Deputy Lieutenant for the County, an elegant modern structure, situated in a small park …

(William Henry was a nephew who had inherited the House from the family although this is not mentioned in the Will of his uncle, the smuggler.)

The description continues:

“… The House has a striking appearance on the approach to it from Canterbury. Its situation is higher than that of the village, and as the plantations are yet young, the building presents its whole front. Behind it the ascent continues, and being clothed with wood, forms a noble background to the whole picture.

“Petham is distant from Canterbury about five miles south-west and from London 56 miles.”

According to the Petham Tythe Awards of 1837 there was over 338 acres of arable and woodland to the Park. Within the immediate grounds of the House are listed a granary, paddock, barn and yard, orchards, two farms and several tenanted cottages.

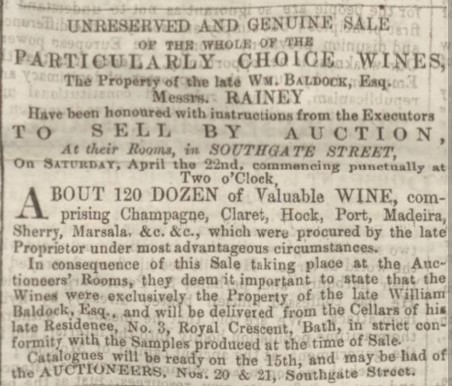

The estate could easily accommodate William Baldock’s passion for racing horses on the Barham Downs and the House appears to have boasted one of the finest cellars of wines and liquors. These were eventually sold at auction 42 years after William Baldock’s death. (See: Intriguing Possibilities.)

The surrounding farm buildings would have been able to hold large stocks of contraband ready for transport to London, Canterbury or Dover. This was typical of the Seasalter Company where impressive houses and out buildings were hidden behind high walls. These staging posts were part of the network’s modus operandi.

Just how important the free trade was in planning Petham is debatable.

William Snr. was now getting older and the nephews managed much of the Seasalter Company’s operations. William also shunned publicity and was not the sort of man who needed to hoard his possessions close by; there was so much land in the form of copses, marshland and pastures to hide cargoes of all kinds, stretching from the Medway to the Deal coast.

The counter-argument is that perhaps Petham House had become necessary to their activities. The privacy and isolation of areas like Seasalter and Graveney marshes were under threat and gradually disappearing. The toll roads had made the North East Kent coast more accessible and there were plans to introduce a rail line to Whitstable, attracting tourists and day-trippers from the cities of London and Canterbury.

But Petham was, first and foremost, the Family Seat for the Baldocks

“… There are paintings by Van Goyen, Loutherbourg, the elder and younger Mieris, Murillo, and some of the Flemish school.”

Although most of the family members had their own properties, they would frequently stay at the house above the village.

When William died, his wife Elizabeth is granted a life interest in Petham but after her husband’s death, she moves to Leigh Villas, Southend, in Essex. Perhaps Petham House was too painful a reminder of their life together or too much for her to manage.

On Elizabeth’s death in 1813, the House passes to William Henry Baldock along with other property not specified in the will. A large amount of this – 700 acres – may have been assets contained in the trusts set up for relatives’ children.

The lands that come into the possession of William Henry might have also included the estates of another nephew (another William Baldock, son of John Baldock, brother of William the smuggler). This inheritance was large. The nephew shows similar business acumen and abilities to those of his uncle. He appears to have a talent for organising and managing business and the free trade interests of the family. We see him rise in stature to step into his uncle’s role when William Snr leaves him some of the best properties and estates in the Baldock portfolio. (See: Baldock’s Smuggling Legacy: Part 1)

Quite why and how William Henry Baldock comes to live at Petham and hold such a large proportion of the Estates is difficult to establish. (In the smuggler’s will of 1812, he is only left 11 acres of land lying in the Parish of St. Mary, Northgate, Canterbury but a sizeable lump sum of £10,000.)

William Henry does build a reputation for himself, however. There are references to him living at Petham in newspaper reports when ‘Mr William Henry Baldock of Petham’ becomes High Sheriff of Kent in 1818. In other news he is described as a ‘gentleman of Petham’ but eventually his fortunes are lost. In 1841, the Canterbury Union Bank collapses and William Henry, a partner, is declared bankrupt.

Because of the bankruptcy, Petham and much of the Baldock inheritance is sold to cover the debts. He retires into obscurity and dies three years later.

References:

An Epitome of County History, Kent (Vol.1) published 1838

Wallace Harvey, The Seasalter Company – a Smuggling Fraternity (1740-1854)

Edward Hasted, ‘Parishes: Petham’, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 9 (Canterbury, 1800), pp. 310-319.

Various newspaper archives including Kentish Gazette

London Gazette Appointments

Pingback: The collapse of the Canterbury Union Bank. The fall of the Baldock empire. | Blue Anchor Corner

Pingback: William Henry Baldock: High Sheriff of Kent 1818. Banker 1830. Bankrupt 1841. | Blue Anchor Corner

Pingback: ‘Hear!’ ‘Hear!’ A heady night with Mr Baldock, the smuggler, at the Grand Conservative Gathering 1838 | Blue Anchor Corner

Pingback: Baldock’s smuggling legacy Part 3: What lies in dark cellars? | Blue Anchor Corner